A House of Crisis

In the United States, reality is framed to legitimize power: the official narrative is central, obedient media reinforce it, and social networks amplify fear and emotion. Truth becomes suspect, personal perception a risk, while beliefs and the desire for protection dominate.

TL;DR

What is currently unfolding in the United States is not merely a succession of violent events. It is a way of narrating reality, of framing it, that reactivates structures characteristic of past authoritarian regimes. The Trump administration is once again deploying classic techniques of imperial legitimation. The Pax Americana ceases to function as an external horizon and becomes an internal mode of governance. The issue is not simply lying, but ordering reality itself—hierarchizing narratives and deciding in advance what deserves to be believed. In Francophone media, this framing is often even more compliant, though more muted. The violence of the discourse is softened; its structure is never questioned. The official version asserts itself as central, the factual as secondary. Reality arrives afterward—when it arrives at all.This dissociation between discourse and experience is nothing new. It has been generalized since Vietnam and now constitutes our cognitive and affective backdrop. The question is no longer what is true, but what—or whom—we choose to believe. The desire for protection takes precedence over analysis. The backfire effect is fully instrumentalized. The more evidence accumulates, the more beliefs harden. Social networking platforms amplify this dynamic by privileging affect. Fear becomes a cognitive shortcut.Truth itself eventually comes to appear suspicious. Trusting one’s own perception becomes a symptom. Our world is a house of crisis, haunted by utilitarian common sense.

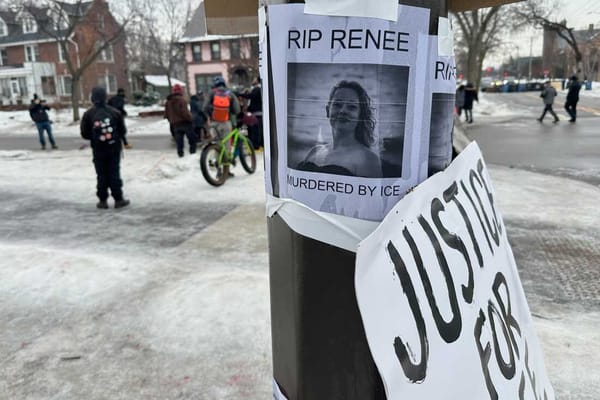

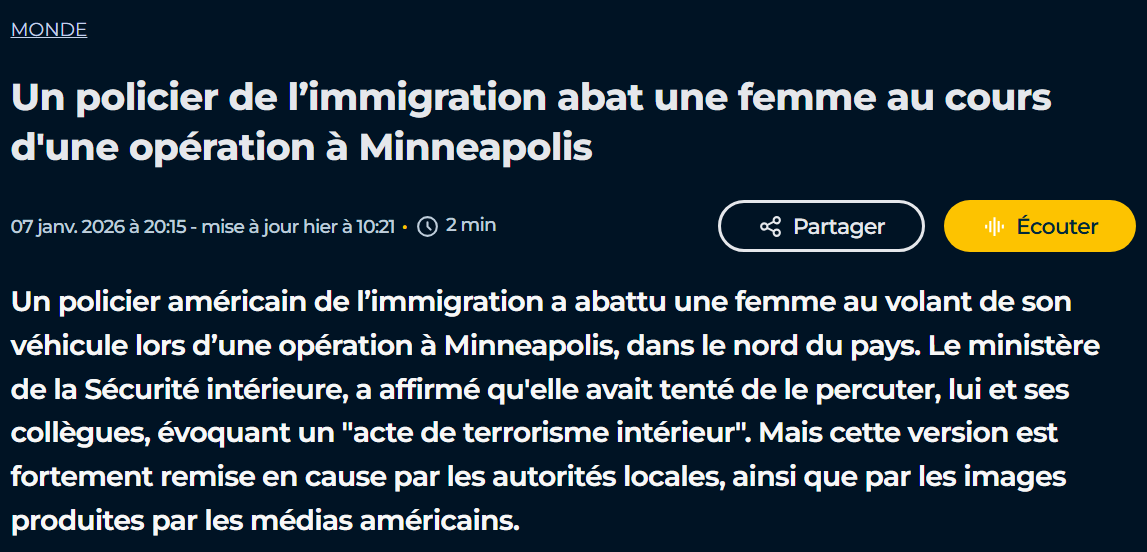

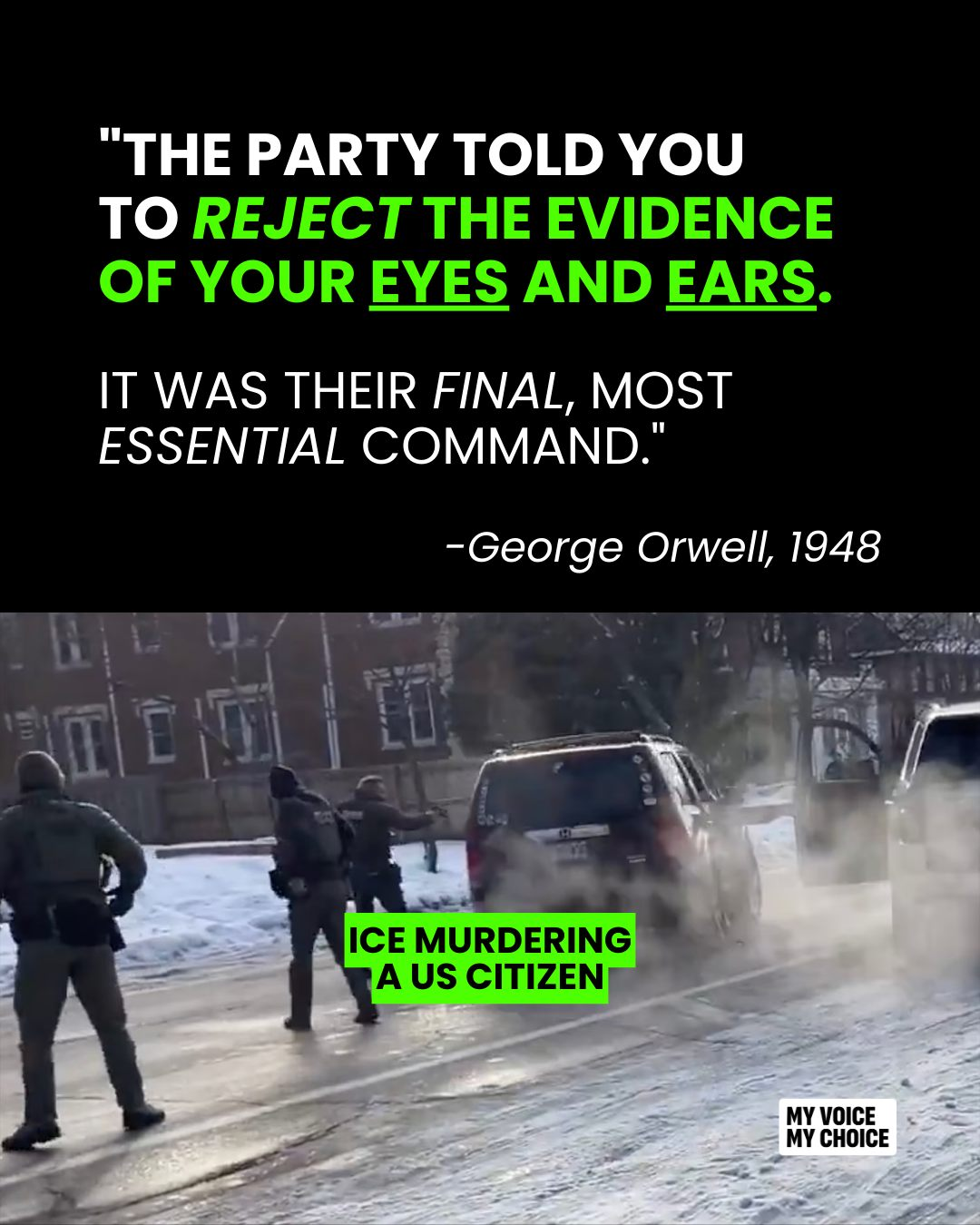

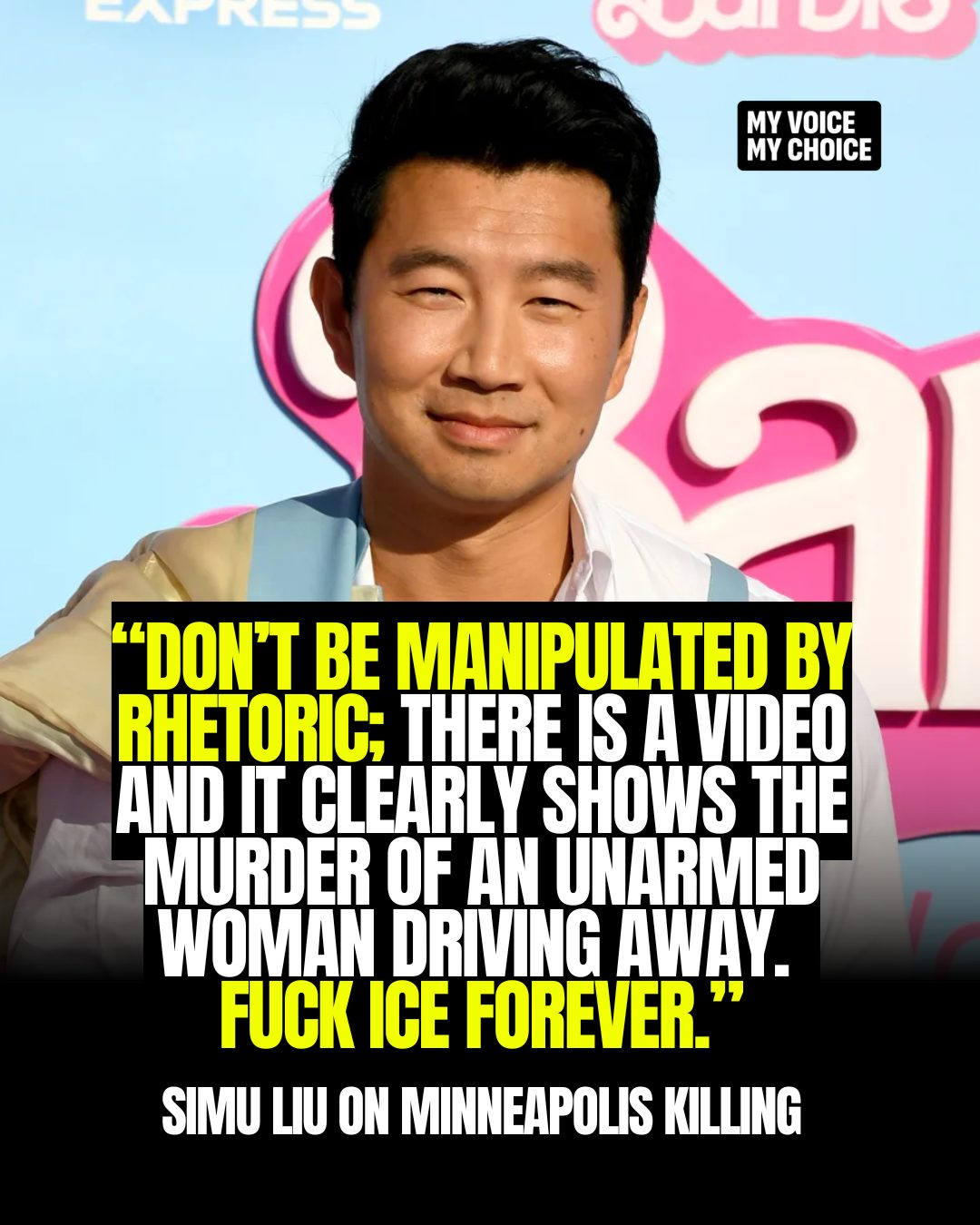

Regarding the events in Minneapolis, the Trump administration once again mobilizes classic justifications of the Pax Americana [[1]], this time within a domestic framework, in order to refound what historians call the Greater American Empire [[2]]: a sphere of economic and political influence, Uncle Sam’s backyard, tinged with freedom and Coca-Cola [[3]]. It does not merely lie; it reframes, orders, and hierarchizes the reading of events [[4]]—down to social media and national news outlets, via press agencies [[5]].

What is troubling here is not only the violence of the facts, but the way they are absorbed, digested, and restituted by the media apparatus. Recent events in the United States—socially, politically, and mediatically—resonate in a literal, amplified manner with what occurred during the rise of the various fascist authoritarianisms of the twentieth century [[6]]. Not through mechanical repetition of history, but through the reactivation of its structures: the naturalization of the state of exception, selective dramatization, the fabrication of internal enemies, and above all a growing disjunction between lived reality and narrated reality.

From a media perspective, the central issue thus becomes the relationship between information and reality, as well as its framing—particularly in French media. What we witness is an enterprise of description and falsification of reality that, in the Francophone space, often appears even more obedient than in the United States, though more subdued, more polished, more “reasonable” in form [[7]]. Where Trumpism embraces narrative brutality, its European media translation tones it down while preserving its structure.

The original title of the piece has been edited for this Belgian news article, yet the hierarchy remained the same after being polished. The official version comes first, and then the factualdepiction of the event. : https://www.rtbf.be/article/etats-unis-un-policier-de-l-immigration-abat-une-femme-tentant-de-le-renverser-avec-sa-voiture-11657900 (translation : Ünited-States : 01.07.2026, An imigration police officer shot a woman "as she was trying to run over him" with her car. / 01.08.2026, An imigration police officer shot a woman during an operation in Minneapolis.)

The systematic priority granted to the Trump administration’s version frames information in such a way that considerable effort becomes necessary merely to denounce its narrative biases, or even its blatant lies. Airtime, article volume, repetition, and the centrality granted to this so-called “official” version constitute it as the dominant narrative, relegating factual accounts of events to the status of supplements, late corrections, or opinions among others. The factual becomes minor not because it is uncertain, but because it is structurally subordinated [[5]].

This process, initiated as early as the Vietnam War [[14]] with the dissociation between official discourse and lived reality, has gradually become generalized. Today, it constitutes the affective and cognitive backdrop of late capitalism: a world in which anxiety is normalized [[8]], obedience is internalized, and recognizing what is wrong already becomes a suspicious act. Information no longer aims to illuminate reality, but to make a world that is no longer livable appear bearable.

The question, then, is not so much what is true as what—or whom—one chooses to believe. The effort targets desire. Would you rather live in a world where the government protects you from far-left terrorists, or in a world where the state dismantles social and economic structures for no reason other than profit, at everyone’s expense? The backfire effect [[9]]—the reinforcement of belief despite contrary factual evidence—is here fully exploited. This cognitive bias, particularly powerful on social networking platforms, paralyzes critical thinking by privileging affect, fear, and symbolic relief over analysis.

In this framework, what actually happens in a video matters little, and the multiplication of evidence only worsens things. The more reality insists, the more inaudible it becomes. Francophone media generally present, in a now routine order, the official version followed by the factual one. The frame is said to be “broad,” but according to an implicit hierarchy that grants central value to the institutional narrative and peripheral value to factual accounts. Reality as such is no longer decisive: it becomes background noise, tolerated only insofar as it does not disrupt the coherence of the dominant narrative [[10]].

This produces a diffuse climate [[8]] of anxiety and generalized obedience. Individuals feel haunted by a world that no longer makes sense, a world rendered illegible. Added to this are the incessant noise of contemporary communication, the asynchronous acceleration of modern media, and now the proliferation of AI-generated content, which further blur points of reference. The result is a paradoxical situation: everyone feels paranoid while being perfectly adjusted to reality. Truth itself comes to seem artificial, while trust in one’s own perceptions is reclassified as a pathological symptom.

Mark Fisher, the British philosopher, develops in his work certain intuitions inherited from French Theory—particularly from Derrida—through what he calls a hauntological reflection [[11]]. This involves being pursued by the ghosts of one’s own life [[12]]: aborted possibilities, cancelled futures, but also the ghost of capitalism itself, which traps subjectivities in a permanent house of crisis. This hauntology is not merely a cultural metaphor; it describes a mode of psychic and social governance, a form of large-scale psychosocial gaslighting that teaches individuals to doubt their immediate experience in the name of a dominant narrative presented as rational, objective, and inevitable.

A useful common sense.

[[1]]: Sarcastic phrasing by analogy with the Pax Romana: a peace imposed by a hegemonic power through its military, political, and economic superiority. In the case of the United States, a corollary of the expression “World Policeman.”

[[2]]: Controversial phrasing referring to the United States’ strategic, economic, cultural, and political sphere of influence since the 19th century, and more specifically its informal (non-colonial) empire since the Cold War.

[[3]]: « L’Empire se matérialise directement dans les désirs de la multitude. » — Michael Hardt & Antonio Negri, Empire, Harvard University Press, 2000, Part 1, Chapter 2.

[[4]]: Foucault, Michel. 2004. Sécurité, territoire, population: cours au Collège de France, 1977-1978. Éditions Gallimard.

[[5]]: Hermann, Edward, et Noam Chomsky. 2020. Fabriquer un consentement: La gestion politique des médias de masse. Investig’Action.

[[6]]: Arendt, Hannah. 2002. Les origines du totalitarisme: Eichmann à Jérusalem. Gallimard.

[[7]]: Bourdieu, Pierre. 1996. Sur la télévision: suivi de L’emprise du journalisme. Liber.

[[8]]: Fisher, Mark. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? John Hunt Publishing.

[[9]]: Swire-Thompson, Briony, Nicholas Miklaucic, John P. Wihbey, David Lazer, et Joseph DeGutis. 2022. « The Backfire Effect after Correcting Misinformation Is Strongly Associated with Reliability. » Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 151(7): 1655‑65. doi:10.1037/xge0001131.

[[10]]: « Le réel n’a pas disparu, il est devenu opérationnel. » — Baudrillard, Jean. 1990. La transparence du mal: essai sur les phénomènes extrêmes. Galilée. & Baudrillard, Jean. 1991. La guerre du Golfe n’a pas eu lieu. Galilée.

[[11]]: Derrida, Jacques. 2024. Spectres de Marx: L’État de la dette, le travail du deuil et la nouvelle Internationale. Seuil.

[[12]]: Fisher, Mark. 2014. Ghosts of My Life: Writings on Depression, Hauntology and Lost Futures. Simon and Schuster.

[[14]]: Klein, Naomi. 2021. La Stratégie du choc: Montée d’un capitalisme du désastre. Actes Sud Littérature. | Page, Caroline. 2016. U.S. Official Propaganda During the Vietnam War, 1965-1973: The Limits of Persuasion. Bloomsbury Publishing.